Initiatives as a Chief Minister

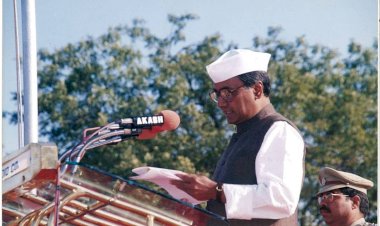

Digvijaya Singh, Former Congress Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh, addressing the National Conference of Dalits at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi in December 2006.

BHOPAL DOCUMENT

Central to this appreciation is the Bhopal Document prepared in January 2002 at a conference held in the State capital under the aegis of the Digvijay Singh government. Sudha Pai suggests that this conference was a historic one that led to the formulation of a new model of development with several significant qualitative nuances. To start with, the author is of the view that it attempted to mobilise Dalits and tribal people and raise their standards of living by helping them chart new paths in economic empowerment through their own initiatives aided and helped by the state. It is suggested that this new Dalit agenda constituted an alternative strategy at gaining Dalit and tribal support through state-sponsored economic upliftment programmes that sought to address the increasing privatisation and liberalisation of the economy through private-public participation.

Shiv Kumar Pushpakar

At a more involved level, the argument questions the limitations of a model of state-led development, which seeks to use political power by the enlightened elite to bring in changes from above for weaker sections of society. Furthermore, there is the contention that the Bhopal Document looked forward from concepts such as Positive Discrimination and Affirmation Action.

Sudha Pai writes: "The BD (Bhopal Document) has significance for the Indian democracy beyond its immediate political impact. Unlike documents in the past it is not merely a list of new policies for Dalits/tribals to be provided by the state. It introspects upon larger issues such as the relationship between caste and Indian democracy, and whether without removing this hierarchical and oppressive institution India can become a substantive and not merely a procedural democracy."Yet at the same time it recognises that in the course of progress towards this goal, a balance is required between the need for maintaining the universal values of democracy and the specific discourse of caste. Too much stress on caste question can lead to differences with groups who could be allies in the democratisation of civil society."

According to the author, two important components of the programme that were developed on the basis of the Bhopal declaration are land distribution and supplier diversity (SD). Though SD was essentially advanced as an administrative initiative during the last financial year (2002-03) of Digvijay Singh's second term, Sudha Pai observes that it has greater political and ideological value in the way it was conceived and implemented. SD stressed the need for the introduction of policies of "diversity" that facilitated suppliership and dealership in the field of business and industry for Dalits in government and private sectors. This apparently had the potential to develop, over time, sections of Dalit and backward communities who have relatively better entrepreneurial abilities. This in turn, it is argued, will help bring down and ultimately remove the marginalisation of these disadvantaged sections from the economic mainstream.

In Sudha Pai's view, this new development initiative is all the more significant in the context of globalisation and the increasing role of the private sector in the socio-economic life of the country. The author is also of the view that sections of the bureaucracy (in the Digvijay Singh regime) were conscientious carriers of the Dalit empowerment agenda. She argues that land distribution to Dalits and the tribal people as well as help from the government to make them retain their hold over the allotted land is required to make SD really effective on the ground.

Obviously, only such a concrete combination between idea and implementation can impart the status of a real path-breaker to this new concept in Dalit empowerment. Notably, the programmes that have come up after the Bhopal Declaration have not been followed up systematically either in Madhya Pradesh or in other parts of the country.

Given the manner in which political forces, including avid advocates of Dalit assertive politics, are grappling with governance and the challenge of adapting Dalit empowerment to changing times, the Bhopal declaration and Sudha Pai's delineation and analysis of the same could well be the trigger for a comprehensive debate, which could throw up more concrete ideas in this direction, adding, deleting or altering some of the tenets of the Bhopal Declaration.

Digvijay's Dalit initiative

POLITICIANS make promises that they rarely fulfil. They make announcements and take positions on sensitive issues that make the sceptics go to sleep. That is, perhaps, the reason why Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Digvijay Singh did not get the kind of Press that his "new age" agenda for the Dalits deserved. At a two-day conference of Dalit intellectuals and social activists he struck a refreshingly bold note on the issue of Dalit empowerment. Of course, some of the 21-points included in the Bhopal Document have a familiar populist ring to them. However, the Chief Minister and the over 500 participants deserve to be complimented for daring to point out the self-limiting and negative aspects of the policy of reservation. The purpose of the exercise may have been to indirectly influence the outcome of the assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh next month. The Samajwadi Party of Mr Mulayam Singh Yadav in the name of social justice has made populist commitments. The Bahujan Samaj Party led by Ms Mayawati has finetuned its Ambedkarite agenda for bluffing its way to possible victory. Mr Rajnath Singh as Chief Minister of the Bharatiya Janata Party-led coalition gave a new dimension to the exploitation of Dalits by offering reservation within job reservations for the most backward castes. And in the absence of a leader of stature Mr Digvijay Singh has been asked to spearhead Congress campaign in UP. The Dalit conference in Bhopal could have been a clever ploy to offer a new deal to the under-privileged sections of society without inviting the wrath of the Election Commission.

Be that as it may, the fact remains that few leaders have had the courage to talk straight on the sensitive issue of reservation of seats for the Dalits. What Mr Digvijay Singh said about the ineffectiveness of the policy of reservation in helping the Dalits break the shackles of economic and social backwardness made a lot of sense. He pointed out that the policy would lose its punch in the near future because the public sector was shrinking. Even if the private sector was made to reserve jobs for the Dalits, it would be able to take care of the economic needs of just 1 per cent of the nearly 17 crore members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes plus those placed in the backward category by the Mandal Commission. After former Prime Minister V.P. Singh unleashed the Mandal recommendations on the nation few politicians have had the courage to question the element of populism built into the present policy of reservation. In fact, mouthing populist rhetoric in the post-Mandal phase helped the likes of Mr Laloo Prasad Yadav, Mr Mulayam Singh Yadav, Mr Kanshi Ram and others to gain acceptability as the messiahs of the Dalits. Mr Digvijay Singh has taken a huge risk by daring to question the long-term consequences of this policy. It is a different matter that the remedy he has offered too stinks of populism. For instance, providing agriculture land to every Dalit family in the state through a series of impractical measures cannot be expected to make the upper castes lose sleep. However, if the Bhopal Document results in a nationwide meaningful debate on the issue, that in itself would be a major achievement and the credit for which should go to Mr Digvijay Singh.

Initiatives as a Chief Minister

मध्यप्रदेश मे काँग्रेस सरकार के शिक्षा सुधार के कार्यक्रमों से साक्षरता दर मे 20 प्रतिशत की हुई रिकॉर्ड वृद्धि

आर्थिक एवं औद्योगिक विकास: समग्र विकास के लिये मध्यप्रदेश की नई आर्थिक विकास नीति घोषित की

Initiatives as a Minister

काँग्रेस सरकार ने किया बेहतर वित्तीय प्रबंधन

Initiatives - A new progressive Bhopal